Martin Heidegger: Being and Time

|

| M.H. |

|

| Hanna Arendt |

|

| Hitler und M. H. |

And yet, very few philosophers have influenced so many branches of philosophy: existentialism, hermeneutics, deconstructionism, postmodernism, phenomenology. And there is little doubt that of the 20th century philosophical tomes, none is as deep and as rich (or as difficult) as Heidegger's Being and Time. (Sartre & Foucault not withstanding.) So lets look at some of Being and Time.

|

In Being and Time, there is a tension set up almost from the start between two possible, mutually exclusive modes of Being in which Dasein might exist. These modes are authenticity (eigentlich sein) and inauthenticity (uneigentlich sein). In the ontology of Being and Time, these two possible modes of existence belong to the essential constitution of Dasein. Dasein must choose these modes of existence. In choosing to be authentic, Dasein chooses itself and wins itself. In inauthenticity, Dasein chooses the public interpretations of the self, takes on the conceptions of the ‘they’ and hence loses itself. It is important to note, however, that these two modes of existence are not directly dichotomous, nor oppositional (p. 67-69). They are not an either/or. Dasein does not choose to be authentic once, and then will forever be authentic. Rather, Dasein must choose again and again whether to be authentic or inauthentic, because these possibilities belong to its essential constitution. The need to choose is constant.

|

| Kierkegaard |

It is important to recognize the constant need to choose because the possibility of authenticity and inauthenticity are constitutions of Dasein, living inauthentically in no way makes Dasein less Dasein. There is no lower degree of being. However, there are distinctions between living the authentic life and living inauthentically, and like Kierkegaard, Heidegger’s conception includes the ‘they.’ What is the ‘they?’ As Heidegger notes, “The ‘they’ is an existentiale; and as a primordial phenomenon, it belongs to Dasein’s positive consititution…” (p. 167). The ‘they’ and ‘they-self’ comprise Dasein in its everydayness. Because Dasein is always in the world, this being-in necessarily signifies being-with others. This being-with is a necessary component of Dasein’s existential everydayness. While Dasein cannot escape this everydayness, it is in this being-with-others where the possibility of inauthenticity lies.

In this being-with-others, Dasein can live in fallenness (Verfallen), which connotes deterioration or a crumbling (Golumb, 1995). Rather than existing on our own terms, with our own defining relation, we accept and incorporate the meanings, which are given to us from the outside. “The Self of everyday Dasein is the they-self, which we distinguish from the authentic Self – that is from the self which has been taken hold of in its own way” (p. 167). We accept the definitions and the responsibilities of the ‘they.’ From this description of the they-self, Dasein has the possibility of laying aside its care, its defining relation and accepting conventional wisdom as its own.

To Dasein’s state of being belongs falling. Proximally and for the most part Dasein is lost in its “world.” Its understanding, as a projection of possibilities of Being, has diverted itself thither. Its absorption in the “they” signifies that it is dominated by the way things are publicly interpreted (p. 264).

Dasein comes to believe given unexamined meanings as important and significant to it, when they in actuality are not. This acceptance of the inauthenticity of the “they-self,” and the laying aside of Dasein’s care is to live in falleness.

In Being and Time, Heidegger examines communication as it relates to inauthenticity and fallenness. In particular, he examines idle talk. Futher in the same passage where he describes falleness, Heidegger continues, “That which has been uncovered and disclosed stands in a mode in which it is disguised and closed off by idle talk, curiosity, and ambiguity” (p. 264). No longer is Dasein concerned with care, its own-most being, nor its defining relation. Rather, in fallenness those are to some extent hidden, as the face of a friend at a masquerade ball – you know who it is, even if you cannot see his face.

In Being and Time, Heidegger examines communication as it relates to inauthenticity and fallenness. In particular, he examines idle talk. Futher in the same passage where he describes falleness, Heidegger continues, “That which has been uncovered and disclosed stands in a mode in which it is disguised and closed off by idle talk, curiosity, and ambiguity” (p. 264). No longer is Dasein concerned with care, its own-most being, nor its defining relation. Rather, in fallenness those are to some extent hidden, as the face of a friend at a masquerade ball – you know who it is, even if you cannot see his face.In everydayness, Dasein is confronted with the possibility of maintaining authenticity or losing it through discourse, because,

this discoursing has lost its primary relationship-of-Being towards the entity talked about, or has never achieved such a relationship, it does not communicate in such a way as to let this entity be appropriated in a primordial manner, but communicates rather by following the route of gossiping and passing the word along. What is said-in-the-talk as such, spreads in wider circles and takes on an authoritative character (p. 212).

In everydayness the pre-conceived and uncritically accepted conventional wisdom, Dasein loses itself. Dasien, by accepting the rules and roles of society’s conventionality, is a leveling down of one’s defining relation. “Every kind of priority gets noiselessly suppressed. Overnight, everything that is primordial gets glossed over as something that has been well known” (p. 165).

The “they” however, as an existentiale, is not some amorphous third person, the herd, or the crowd. In fact, despite the term’s third-person implication, the “they” is in fact intricate to being Dasein. Rather, the “they-self” is an act, a way of being Dasein, accomplished by Dasein’s accommodation of the interpretations of the self and the world, through idle talk, curiosity, novelty and ambiguity. “If Dasein is familiar with itself as they-self, this means that at the same time the “they” itself prescribes that way of interpreting the world and Being-in-the-world which lies closest” (p. 167). Living in the “they” then, is not the fault of some third party, but is Dasein’s responsibility. If Dasein projects itself into the future based upon the internalized categories supplied by the “they,” it is by default self-limiting – Verfallen.

The trick is for Dasein to live as an individual and in the everydayness of Verfallen (Guignon, 1984).

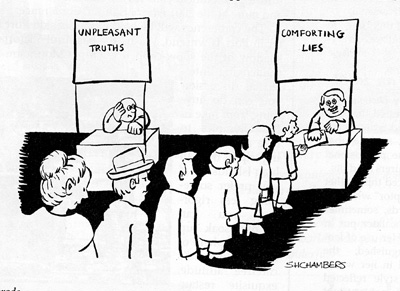

The trick is for Dasein to live as an individual and in the everydayness of Verfallen (Guignon, 1984). Of course given all this great thinking...how was he able to join the most malevolent political party ever? Perhaps Martin had the most pronounced version of cognitive dissonance ever.

And since this is the last of the philosophy books series, here are the links to the previous nine for your perusal.

Number 9: Ion by Aristotle

Number 8: Care of the Self by Foucault

Number 7: The Ethics of Authenticity by Charles Taylor

Number 6: I & Thou by Martin Buber

Number 5: The Communist Manifesto by Marx & Engels

Number 4: The Reasons of Love by Henry Frankfurt

Number 3: Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing by Soren Kierkegaard

Number 2: The Rebel - Albert Camus

Number 1: The Theory of Moral Sentiments - Adam Smith

No comments:

Post a Comment